- Sati

- Posts

- 🔀 Recognize when to pivot to a venture scale business model

🔀 Recognize when to pivot to a venture scale business model

A series on market creation (Part 3): building and scaling Kobo360

Welcome to Sati - Sourcing Africa to Invest

👋🏾 I’m Marge… ethnically Ugandan 🇺🇬 raised in the US 🇺🇸 and a dreamer 💭

I’m joined by Ona…also Ugandan 🇺🇬 working in the UK 🇬🇧 and honestly, she’s a rockstar! This publication could not take place without her.

Here at Sati, we’re on a journey to uncover Africa’s history of tech and private investment to understand the present and predict the future.

Join us; let’s see where this ride takes us 🚌

Wow… it’s been a hectic time!

Ona just wrapped up finals, and we both moved at the end of June…

Hence why it’s been a while since you last heard from us.

But we’re finally back!

And we’re glad to have you here!

If you’re new to Sati, you’re joining us at the tail end of our 3 part series on Kobo360.

Here’s what you missed:

Part 3 is all about building and scaling.

Before we jump in, we want to set the record straight

In researching Kobo, we did a deep dive into the freight forwarding industry and its players.

We shared a market map on Twitter.

And the beauty in sharing publicly is that people with more knowledge can comment on your content to help refine your thinking.

That’s precisely what the team at Jetstream did.

They helped us decipher the difference between a freight broker and a freight forwarder

Freight broker: freight brokers are middlemen that connect cargo owners with freight carriers (trucking companies, shipping vessels, cargo planes, etc.) to get goods from point A to point B in a timely and cost-efficient manner.

Freight forwarder: freight forwarders do many of the same tasks as freight brokers. But they also deal with warehouse planning, providing cargo insurance and customs brokerage services, as examples. They do not own the freight, but they do assume legal responsibility for goods once in their possession (the main differentiator between forwarders and brokers since the latter never physically handles the movement of freight).

So in summary, Kobo is a freight broker.

Now that we’ve cleared that up, let’s wrap up this series on Kobo!

This is the version of Kobo that most of us know; the Uber for trucks that launched in 2017/2018.

But their story actually begins well before.

They weren’t initially a freight brokerage.

Their first service… local and international delivery.

Let’s go back in time.

Product 1: Local and international delivery

The problem

It’s 2016.

Nigeria had more than 75 million businesses and over 190 million people who needed things moved around every day.

The main option for delivery was through international players like DHL, UPS, and FedEx. There existed a few smaller players as well.

But these providers didn’t sufficiently cover the needs of individuals and SMEs:

Options for inner-city shipments were limited

Delivery to rural areas was essentially non-existent

Shipping was expensive and pricing wasn’t transparent

Scheduling was unreliable

Delivery could take several days if not weeks

There lacked available information on foreign exchange to process international shipments

Hence, Kobo spotted an opportunity.

They planned to become the first home-grown company to handle local last-mile and international packages, mail, and parcel.

The solution

To help individuals (B2C) and SMEs (B2B) move packages, Kobo needed two things:

A technology platform

Assets to move the goods

Building a technology platform was a no brainer.

But they had to decide if they would acquire their own fleet or partner.

Kobo decided to be asset-free

The decision to be asset-free and partner came from Obi’s experience at Uber.

Uber’s success in Nigeria proved to Obi that Kobo could leverage a similar model.

Therefore, Kobo built a two-sided digital marketplace for shipping goods.

Beta started on April 17th, 2016.

On one side of the marketplace were individuals and SMEs who requested for packages to be picked up on-demand or by scheduling.

On the other side were delivery partners like:

DHL, UPS, and the like

Independent commercial and private drivers, as well as air travelers

**Note: As a semi-aggregator, Kobo was not in direct contact with the recipients of goods.

DHL, UPS, and individual air travelers handled international shipments.

Local shipments were delivered via:

Bikes for last-mile delivery

Vans for items fairly above 20 kgs

And trucks for moving large cargo

Upon customer request, Kobo either picked the best route or shared the request with providers who would bid for the delivery.

What needed to be true for Kobo to win in this space?

Like any two sided-marketplace, Kobo’s success was reliant on the number of partners it could command on its portal.

The incentives for partners were more potential customers.

The incentives for customers were convenience, affordability, and speed.

Therefore, Kobo’s solution solved for:

Affordability: Kobo was ~40% cheaper. They got discounts from partners for meeting certain volume metrics. They then transferred that value to customers. Moreover, high volume drove competition among partners thereby making logistics more affordable.

Volume: Kobo’s biggest partner at the time was Chisco, a luxury bus company. Chisco allowed Kobo to set up shop on their premises, which ensured constant fleet. By managing Chisco’s logistics, Kobo helped grow the company's revenue by over 340%.

Availability: Kobo had 200 fleets carrying parcels with local and international destinations.

Speed and Safety: Kobo guaranteed safe delivery of goods within 48 hours locally and 72 hours internationally.

Go-to-market

The team was scrappy.

After their successful 3-month beta, they were on a mission to drive customer acquisition.

So on September 1st, 2016 they announced an offer for free local and international deliveries of 1000kg packages for 500 SMEs.

The objective of the promotion was to build brand awareness and hook customers on two main aspects of their value proposition: speed and affordability.

To maintain momentum, they continued to run promotions in 2017.

They ran promotions as a delivery partner for brands.

And also ran a referral program.

Despite their effort to drive awareness through social media, their engagement was low on most platforms excluding Instagram

In summary, Kobo ran a lot of tests and learned a lot

Let’s recap their offerings.

Above, we laid out:

International delivery through UPS, DHL, and individual travelers

Local and last-mile delivery through partners with bikes, cars, buses, vans, and freight trucks

A few other offerings included:

Moving services

Consulting services that involved building websites, CRMs, and payment solutions

Kobo did it all.

And while things seemed chaotic, they were delivering results.

But after a year, the team realized they needed to pivot

In Nigeria at the time, most commerce happened offline.

And for local last-mile delivery to work, the team had to drive significant volume.

Remember, Kobo dabbled in delivering goods with freight trucking partners and realized that the transaction value was much higher:

Last mile = $10-50

Long haul = $1,000+

Therefore, Kobo pivoted to the version of the business we know today:

The asset-free Uber for trucks —> aggregating cargo owners, truck owners, drivers, and cargo recipients.

Product 2: Uber for Trucks

The pivot didn’t come without its issues.

The trucking industry was fraught with challenges:

Cargo loads would take days to be released from the port

Routes that should take three days would require significantly more time because of poor infrastructure

Fleet owners would charge double due to the challenge of reverse logistics as there was often no cargo to bring back from point B once a delivery was made

If you want to dig deeper into the challenges, we wrote about them here.

But, Kobo found gold:

A sector desperate for innovation

A problem big enough to drive venture scale returns

A proof of concept through previous testing

Kobo’s new business model was born. They knew they had a value proposition if they could address these issues.

But truck owners were hesitant to take on trips offered by the then-unknown Kobo360.

To make things happen, they had to land a big client.

Winning their first big client

In 2017, Kobo approached Honeywell to get the US conglomerate to test its on-demand trucking service.

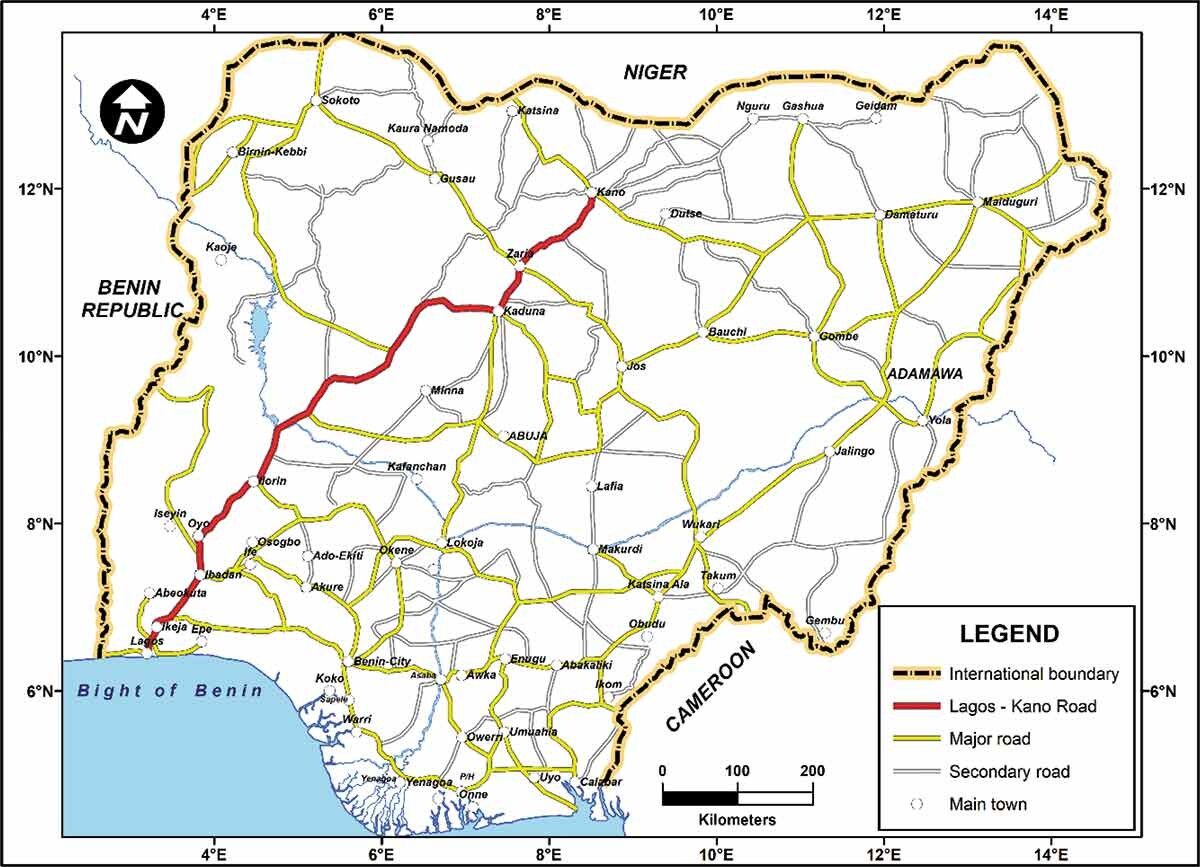

As a pilot, Honeywell asked Kobo to find six trucks for the Lagos–Maiduguri route.

The route went into the heart of an area plagued by the terrorist organization Boko Haram, where truck drivers often lost entire loads to the militant group.

Kobo delivered four trucks within 48 hours.

Honeywell gave them another route to Bayelsa state in the south.

This route had Niger Delta militants who extorted money from truck drivers.

To get truckers to take the route, Kobo had to pay drivers upfront, which they managed to do by borrowing from relatives and friends.

In the end, Kobo completed 62 trips in three weeks and won a four-year contract with Honeywell.

Shortly after securing the contract with Honeywell, Kobo got truck brokerage deals with Olam, Unilever and DHL.

Applying to YC

Knowing that they had fallen upon and operationalized a business model that could revolutionize traditional logistics in Africa, the team applied to YC’s summer’18 cohort.

During their interview, Obi was aksed “What’s holding you back from becoming a unicorn?”

Obi’s response: “Working capital.”

Kobo got into YC and raised the capital they needed.

Their pre-seed round was $1.2 million led by Western Technology Investment with participation from Future Africa.

Moving to Kano

In May 2018, Obi and Ife made the bold decision to uproot their families and relocate to Kano.

Kano was a key destination for the industry because:

480 trucks moved through the Lagos-Kano corridor daily

82% of truck owners and drivers in Nigeria came from the North

Obi and Ife moved to have on the ground presence and get truckers on the platform to ensure they could meet the demand of their growing list of clients.

They would be up at 3am, go to truck parks and talk to truck owners.

They explained how there were a lot of cargo owners in other parts of the country desperate for trucks to move their goods.

The incentive for truck owners to be on the platform was to expand their business.

Once truck owners saw that Kobo’s platform was reliable, word of mouth spread.

Building the new platform

Before Kobo, Africa’s $150 billion logistics sector was very informal.

To move cargo, businesses were reliant on telephones, opaque pricing, and expensive middlemen, making it challenging to move goods efficiently.

To combat this, Kobo developed an app that matched business requests with a selection of quality trucks of all categories, anytime, with service delivery guaranteed.

How the app worked for each party:

Cargo owners:

Requested trucks of different sizes based on the size of their load

Had access to a tracking feature that allowed them to view the journey of their cargo from point A to B

Truck owners:

Had a wider range of access to cargo loads

Could leverage KoboWIN, which gave access to financing to expand their fleet

Truck drivers:

Received 50% payment upon loading

Had consistent business and scheduling reliability

Had access to rapid-response repair teams which was important because 92% of trucks in Africa are purchased used making these trucks prone to quality issues

Had immediate access to authorities in the case of hijackings or bandit attacks

Had access to training

All users:

Had access to SMS enabled communication in areas that lacked internet

Could engage in their ethnic language and could leverage voice (for users that didn’t know English or were illiterate)

The app had a first-of-its-kind bidding tool for both drivers and cargo owners to assess the price of a trip before selection

Payments and scheduling were handled directly on the platform

The platform showed the time it takes for a submission to go from request —> acceptance —> position —> loading —> transit —> delivery —> invoice —> to payment

View of the dashboard

Expanding: both geographically and technologically

Raising their seed round

In December 2018, they raised a $6 million seed round led by the IFC with participation from TLcom Capital and Y Combinator.

Funds would be used for the following:

1) To expand into Ghana, Togo, and Cote D’Ivoire with existing clients

The team officially launched in Togo in January 2019 and in Ghana in March. They ended up not expanding into Cote D’Ivoire at this time and instead entered Kenya in August.

2) To implement specific features clients wanted to add to the platform

Clients wanted to have more visibility related to the movement, tracking, accounting, and sales of their goods. They also wanted to be able to integrate other services (e.g., SAP) into the Kobo platform.

In response, Kobo developed an API that large enterprise customers could leverage.

3) To build more physical presence throughout Nigeria

Kobo wanted to open 100 hubs before the end of 2019 to help operators collect proof of delivery, monitor trucks on the road, and have closer access to truck owners for vehicle inspections and training.

They also wanted to add more warehousing capabilities to support reverse logistics. This would help bring prices down by matching trucks with return freight after dropping a load.

4) To expand programs and services for drivers. Drivers would have access to:

KoboCare, which created group health insurance for drivers and had an incentive-based program that gave drivers a 5,000 Naira bonus per trip for their kids’ school fees.

Discounted petrol

Raising their series A

In August 2019, they raised a $20 million series A led by Goldman Sachs with participation from Asia Africa Investment and Consulting Pte., TLcom Capital, Y Combinator, and the IFC.

Shortly thereafter, they received $10 million in working capital from Nigerian commercial banks.

At this point, the version of Kobo as we know it (Uber-for trucks) had been operating for ~2 years.

They were in Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, and Kenya with a fleet of more than 10,000 drivers and trucks using its app.

Funds from this raise would be used:

1) To add 25,000 drivers to the platform

2) To expand the team

3) To strengthen their extensive network of clients and truck owners across the continent

4) To train drivers to use the mobile-enabled technology so that they could complete trips seamlessly and earn more money

5) To continue their expansion across the continent

6) To build a Global Logistics Operating System (G-LOS), a blockchain-enabled platform that would combine all activities in the supply chain into one robust system.

COVID shook things up

In the first two days of the shutdown, Kobo’s trips were down ~84%.

Due to lack of clarification from the Nigerian government on what was deemed essential movement, 3,000 trucks were parked as drivers feared being arrested, attacked, or having their goods impounded by law enforcement.

Moreover, volume of goods across the continent declined ~30%.

The overall underutilization of Kobo’s pool of truck drivers led to lost revenue.

They also saw increased costs to run trips.

Truck drivers suffered additional fuel expenses, increased mileage per trip; and truck and cargo security raised their monthly costs.

Lengthy turnaround times put financial pressure on drivers, causing many to default on loans.

Lastly, there was slower movement of cargo.

For example, the mandatory testing at Kenya-Uganda borders reduced driver clearance.

Usually, it took between 4 hours to a full day to clear drivers. But 48 to 72 hour delays occurred because drivers had to be tested and receive their results before proceeding.

Despite these challenges, Kobo did its best not to pass incurred extra costs to end users.

The launch of their Global Logistics Operating System was timely

G-LOS officially launched during COVID in August 2020.

No different from Kobo’s original application, it connected businesses with transporters.

However, the platform enabled end-to-end digitization of the entire supply chain, increasing efficiencies, reliability, and visibility.

Its remote access to the supply chain allowed for business continuity.

The platform facilitated social distancing practices, enabling drivers to secure all jobs with cargo owners through the app.

One of the most important aspects of the implementation of G-LOS was that it allowed Kobo to move ~47% of its customers to digital proof of delivery, a previously analog process.

Despite G-LOS, Kobo had to pivot to fight the impacts of COVID

Although 2019 was a good business year, COVID affected Kobo’s operations.

Obi shared some of the struggles he faced as CEO at the time.

He went on leave to take leadership courses to improve his capacity because he felt like he didn’t have the ability to run the company anymore.

Obi did stay on as CEO.

But to get through COVID, the company made a slight pivot and worked with insurance firms to invest over $4 million to build an insurtech product that tackled the risk of goods-in-transit, driver misbehavior, and credit default.

Raising their series B

In December 2021, Kobo raised a $48 million series B in equity and debt, half of its fundraising goal for the round.

The round was led by the Fund for Export Development in Africa (FEDA) with participation from TLCom Capital, IFC, Goldman Sachs, and other bank and insurance partners.

Kobo developed Payfasta, an embedded finance platform, to fix its delayed revenue collection problems.

The company deployed $100 million through Payfasta and actively financed truck drivers and partners faster than before. Its nonperforming assets dropped to 0.8%, profit margins went up 240% and the receivables cycle reduced by 64% from 138 days to 49 days.

Obi mentioned that in the early days of scaling, they weren’t focused on profitability and ate up all costs. But they started passing costs to transporters and field operations.

Through their insurance and new fintech product, they moved towards positive unit economics.

Kobo today

Management has changed.

In 2022, Ife resigned due to "personal reasons."

He was replaced by Phyllis Kemide Senah, an ex-Citi Bank and Google c-suite employee, who also left the company in November 2022.

Kobo has been the Uber for trucks for 6 years.

They’ve worked with 50,000+ truck drivers to help them transport over 760 million kilos of goods, worth an estimated $200 billion for over 1,000 clients.

What learnings stand out?

Know when to pivot: Kobo360 started out as a local last-mile and international delivery company. A year in, they pivoted to freight brokerage for trucking, a business model with much higher margins.

Be strategic with how you use capital: the founders always had clarity on how they planned to use funds raised to scale.

Ambition should drive you: ambition is the strong desire to achieve something, typically requiring determination and hard work. The team had ambition, and it plays into their success today.

We hope these learnings stand out to you too! But if there’s anything else that catches your eye, feel free to share your thoughts with us.

Our partnership with Zedi Africa

If you’re in need of marketing, customer acquisition, or talent hiring services, reach out to Zedi Africa here.

Make sure to use the “SATI” discount code (last question of the form) for 5% off on their services.

Future Events

Jas and I have office hours on August 2nd with Joe Kinvi from HoaQ Club. Sign up to join us!

That’s all we have for you this week!

Thanks so much for making it to the end!

In 2 weeks we’re shifting gears, taking a step back, and looking at Africa from a birdseye view.

If there’s anything else you’d like us to explore, send me a note. I’d love to hear from you! You can find me on:

If you enjoyed this piece, make sure to sign up to get more like this in your inbox soon!

Until next time!

👋🏾 Ona and Marge

Reply